SHIDEH GHANDEHARIZADEH / NEXTGENRADIO

What is the meaning of

home?

Nora Colie speaks with Sean Cruz, who has taken it upon himself to uphold the legacy of Indigenous jazz musician Jim Pepper.

Finding Home in the Legacy of a Beloved Indigenous Musician

Listen to the Story

Click here for audio transcript

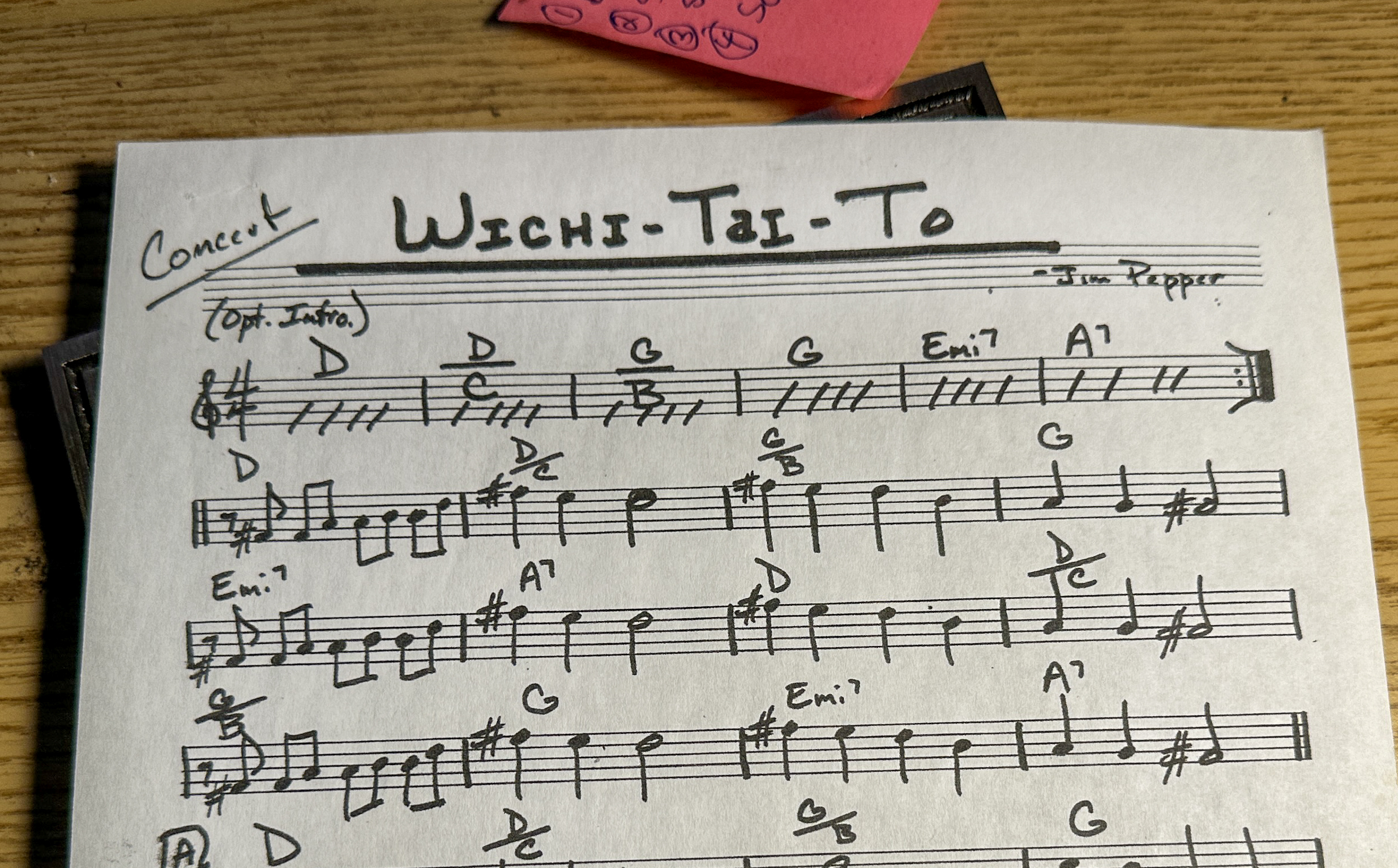

[Saxophone solo from Jim Pepper’s “Witchitai-To” plays]

Sean Aaron Cruz: There’s no one that plays like Jim Pepper.

The song he’s remembered most for – not for its beauty and its power – but it has medicinal value and people all over recognize that.

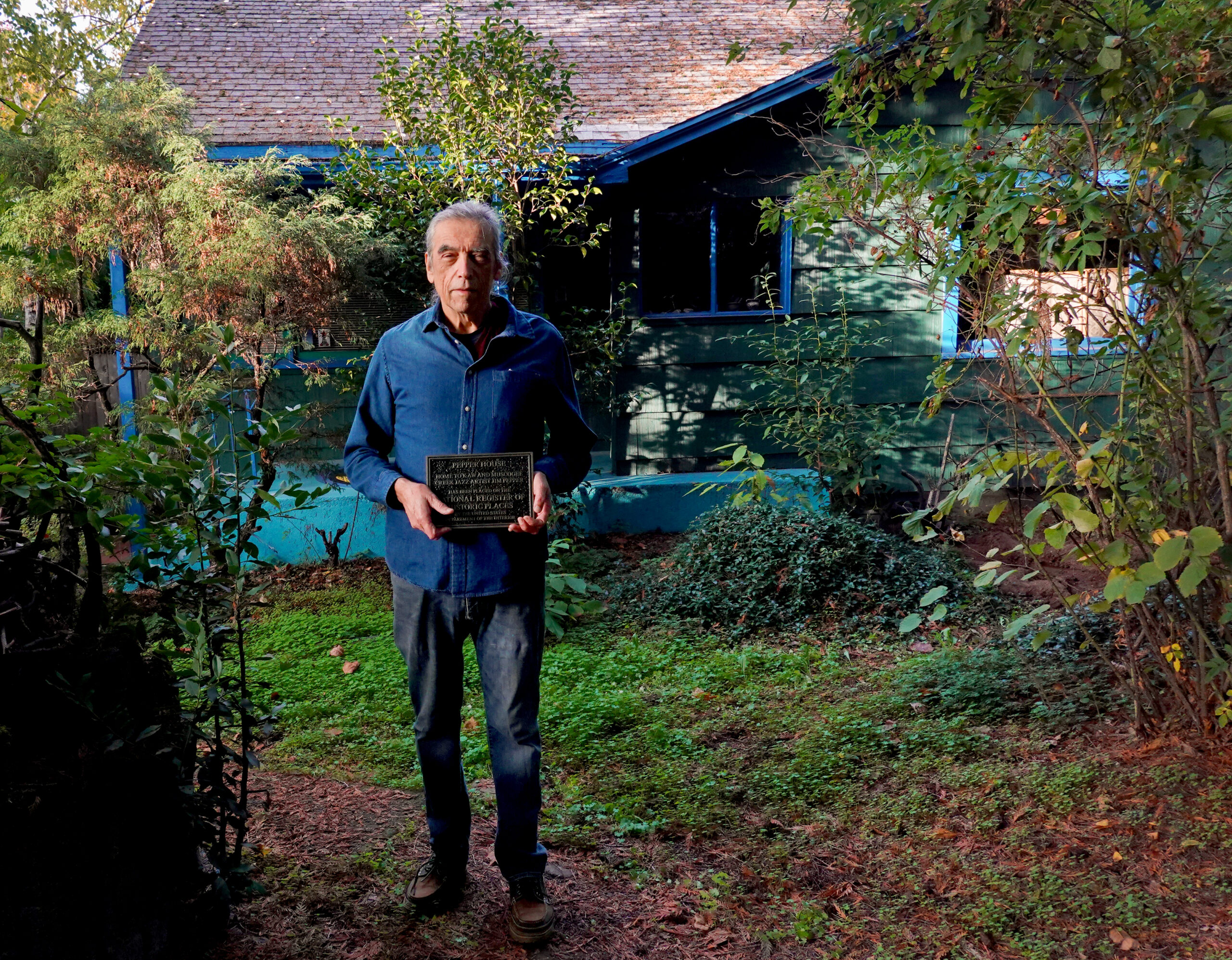

My name is Sean Aaron Cruz. and my indigenous roots are in Central Mexico. And we’re meeting here in what is now known as the Jim Pepper House.

I bought it from a developer

I had heard of Jim Pepper by reputation but I didn’t know if I’d ever heard his music before.

One day I was minding my own business standing in the front yard, there by those cedar trees, and this car stopped and this lady said, “Hi. We used to live here. My mom would love to see the old house again. Could I bring my mom?” Well, sure.

And, the following week, she brought Floy over. And she gave me a gift. It was her bootleg CD of her son’s first LP, Jim Pepper’s Pow Wow, 1971. And I put it on as soon as they left.

And it starts with a traditional chant, no band instruments.

[Witchitai-To chant]

And then the second track started to play. And it started to bring up a powerful memory. I couldn’t place it.

[Jim Pepper’s jazz-fusion Witchitai-To plays]

So I picked the CD up, and I’m looking at it, and I mean, “Who is this?”

And I saw that the guitar player on the date was Larry Coryell. And I just immediately thought of the one time I saw Larry Coryell live. That was about 1970.

And Coriel says, I want to feature my tenor player on this next song.

“He’s an Indian, a real Indian.”

I never forgot the introduction, but I did forget his name. And he came up to the

front of the stage, and I remembered, you know, like studying him. Ribbon shirt and eagle feather. And he started playing this song.

[Jim Pepper’s jazz-fusion Witchitai-To plays]

Everybody up off the floor. Everybody up dancing, singing, chanting. Everybody.

And that song is named Witchitai-To.

The lyric is “Water spirit feelin’, springin’ round my head. Makes me feel glad that I’m not dead.”

That’s the whole lyric. Just that. Makes me feel glad that I’m not dead.

I’d looked for him for years and eventually gave up.

So here’s some 30 years later. I met his mom, I’m living in his house and she gave me the record I was looking for that night.

At that time in 2002 I’d been living with depression for six years.

The thing about Jim’s music – particularly the song Witchitai-To and that line, “Makes me feel glad I’m not dead” – that has reached lots of people and it reached me too.

The house changed the trajectory of my life from being in a place where I was always having to look for reasons to live to where I became glad I’m alive.

This home is like a family. That’s what it is. The home is like a family.

I can’t imagine living anywhere else.

Sean Cruz’s home is a striking mosaic of vibrant colors, family photos and memorabilia.

The front two rooms inside the home boast walls of turquoise, with accents of purple trim and doors; the kitchen has splashes of lime green, royal blue and fiery red, and the back room is awash in a warm orange.

“Colors are important,” Cruz said. “Color therapy.”

Sean Cruz, a former real estate agent, felt something powerful when he walked into the Pepper house. Instead of selling it, he bought it. Three months later, Cruz learned it once was the home of Jim Pepper, the Indigenous jazz musician he had searched for for years.

NORA COLIE / NEXTGENRADIO

Framed pictures of cherished family and friends intermingle with posters, pictures and memorabilia of the legendary Native American jazz musician, Jim Pepper.

NORA COLIE / NEXTGENRADIO

Framed pictures of cherished family and friends intermingle with posters, pictures and memorabilia of the legendary Native American jazz musician, Jim Pepper. Throughout the space, makeshift shrines pay homage to Pepper, who grew up in Portland, Oregon. Tributes are scattered across nearly every surface — a sage stick, thoughtfully placed between two of Pepper’s CDs, propped against the wall, and an assortment of rocks, sticks and letters from senators and government officials regarding Jim Pepper’s legacy.

This home has given him a reason to live.

“If a family lives in a house that long, there’s something about the family that’s just imprinted in it.”

“There was something about this house that was talking to me,” Cruz said, who first came across the house when he was a realtor in 2002. “It was really strange. I liked everything about it and the way it felt.”

So instead of selling the house as his own listing, Cruz bought it for himself.

Just weeks after buying the house, that special feeling for the house became clear when he met the family that had lived in it for four generations.

“If a family lives in a house that long, there’s something about the family that’s just imprinted in it,” Cruz said.

The family that had lived in the home were The Peppers. They were an Indigenous family of Kaw and Muscogee Creek heritage. Floy Pepper was a prominent Native educator of Oregon, and her son, Jim Pepper, achieved global recognition as a prominent jazz tenor saxophonist during the 1960s and ’70s. Jim Pepper also happened to be a musician that had left an undeniable mark on Cruz in 1970.

Since buying the home, Cruz has been dedicated to protecting The Pepper family home and preserving the music and legacy of Jim Pepper.

Sean Cruz bought the Parkrose home in 2002. “I didn’t know anything about the house’s history at all,” said Cruz. “I liked the way it felt to be here.”

NORA COLIE / NEXTGENRADIO

MEETING THE PEPPER FAMILY

Three weeks after Cruz moved into the house, he had some unexpected visitors. A mother and daughter, Floy and Suzie Pepper, stopped by and told Sean his house had been their family’s home for generations

Cruz let the mother and daughter tour their former home. As a gift, Floy, Jim Pepper’s mother, gave Cruz a compact disc of her deceased son’s music.

The 1971 LP Jim Pepper’s Pow Wow was Jim Pepper’s debut solo album. It was originally released on Herbie Mann’s Embryo label.

NORA COLIE / NEXTGENRADIO

“It was a bootleg CD of his first LP, Jim Pepper’s Pow Wow, 1971,” Cruz said.

The musician’s name rang a bell, but Cruz couldn’t quite place it — until he pressed play on his CD player. Cruz said an overwhelming feeling came over him. The music unlocked something deep within him, rekindling a long-lost connection.

“I actually wandered out of the house when the record started and [the music] brought me back in,” Cruz said. “I picked the CD up and I’m looking at it [thinking], ‘who is this?’”

Cruz recognized some of the names of the jazz musicians on the back of the album cover. It included musicians he had listened to in college, including guitarist Larry Coryell.

SEEING JIM PEPPER PERFORM

Almost thirty years before, in the early 1970s, Cruz had gone to a Chuck Berry concert in a roller skating rink in San Rafael, California. The opening act was the jazz musician Larry Coryell and his band. “I want to feature my tenor player on this next song,” Cruz remembered Coryell saying. “He’s an Indian, a real Indian.”

Cruz never forgot that introduction of Jim Pepper. The tenor saxophonist started playing and instantly a wave of enthusiasm washed over the crowd, igniting a fervor of dancing, singing, and joyful chanting.

After the show, instead of heading home, Cruz headed for the Tower Records in San Francisco to try to find the music by the tenor saxophonist. Unfortunately, Cruz couldn’t remember his name, but he knew what Pepper looked like, and Cruz was sure he’d find his work in the Larry Coryell section. But Cruz didn’t. For many years he tried looking for the song and the musician but eventually gave up.

Jim Pepper’s song “Wichi-Tai-To” is derived from a peyote healing chant. The song celebrates the healing power of the water spirit. It’s the only song in the history of the Billboard pop charts to feature an Indigenous chant.

NORA COLIE / NEXTGENRADIO

Jim Pepper’s song “Witchitai-To” fuses the jazz-rock fusion music style he was known for with his Indigenous roots.

REALIZING HE LIVED IN JIM PEPPER’S HOME

The album Floy Pepper gave to Cruz starts with a traditional Comanche chant, but it was the next song, titled “Witchitai-To,” that jogged Cruz’s memory.

“I knew who it was,” Sean said about the musician he had been searching for years earlier. “It was him!”

The lyrics to the song, sung both in Comanche and English are: “Water spirit feeling springing round my head, makes me feel glad that I’m not dead.”

Cruz says the music is not only beautiful, it also has medicinal value.

“At the time, in 2002, I’d been living with depression for six years and I had suicidal periods,” Cruz said. “I got to a place where, for me, it was all about finding reasons to live. I had to find reasons to live.”

The lyrics became Sean’s mantra.

PRESERVING JIM PEPPER’S LEGACY

Cruz promised Jim Pepper’s mother, Floy, before she died, that he’d do everything he could to see that her son got the recognition he deserved.

Working with former Oregon State Senator Avell Gordly, Cruz helped draft Senate Joint Resolution 31, a bill that honors Jim Pepper’s life and achievements. Cruz also went on to found the Jim Pepper Native Arts Council, a nonprofit with a mission to improve access to culturally relevant music education in Jim Pepper’s name. The group also produces the annual Jim Pepper Native Arts Festival, a celebration that features Indigenous artists and musicians.

“I’m planning to get carried out of here like Jim.”

Cruz also made sure the Pepper family home will be preserved for its historical significance. protected in perpetuity.

“Floy Pepper shared with me that both Jim and his father passed in the house. They both did,” Cruz said. “And so this place had to be protected, and the way to do that is to get it on the National Register.”

With the help of City of Portland staff and letters of support from federal, state and local officials, including United States Secretary of the Interior, Deb Haaland, the Pepper House was placed on the National Register of Historic Places in July 2023.

The home is like a family to him, and he can’t imagine living anywhere else.

“I’m planning to get carried out of here like Jim,” Cruz said.

The former home of Jim Pepper was placed on the National Register of Historic Homes in July 2023.

NORA COLIE / NEXTGENRADIO