LAUREN IBANEZ / NEXTGENRADIO

She used to stand in line for services when she was unhoused; Now, she provides them

Listen Here

Click here for audio transcript

Barbra Weber: I lived by this metal box over here, on that corner there for almost two years, back and forth down the street, but mostly right there next to that metal box.

My name is Barbie or Barbra Weber.

To me, the adjective that you use — homeless, houseless — it doesn’t really matter because I’ve never had a problem with words. What I have a problem with is what everybody attaches to that word, because I’ve been homeless my entire life. I’ve never owned a house. So the vernacular of what you use doesn’t really matter, you know?

[[BARBRA LAUGHS]]

[[BUSES, CARS AND TRAINS]]

So we’re at Hazelnut Grove. Hazelnut Grove is a self-governed community in the middle of the city of Portland. I had an altercation with one of my camp mates, I got punched in the face. So I got into Hazelnut Grove on domestic violence or protection. And then I applied to stay and I got in February of 2020. So I’ve been there almost four years now.

[[CHAIN LINK FENCE OPENING]]

We have dogs, you may get barked at!

[[DOGS BARKING SOUNDS]]

This here, we have infrastructure, we have houses, we have doors that lock. A camp is a tent. You’re camping in a tent. None of this is camping.

[[DUCKS QUACKING]]

We have grass and animals. This is life. This is like a neighborhood.

[[POWER GENERATOR IN BACKGROUND]]

[[DOOR SLOWLY OPENS, CREAKING]]

Come on in. I put my dogs outside so they didn’t jump all over you.

[[DOOR CREAKING CLOSED]]

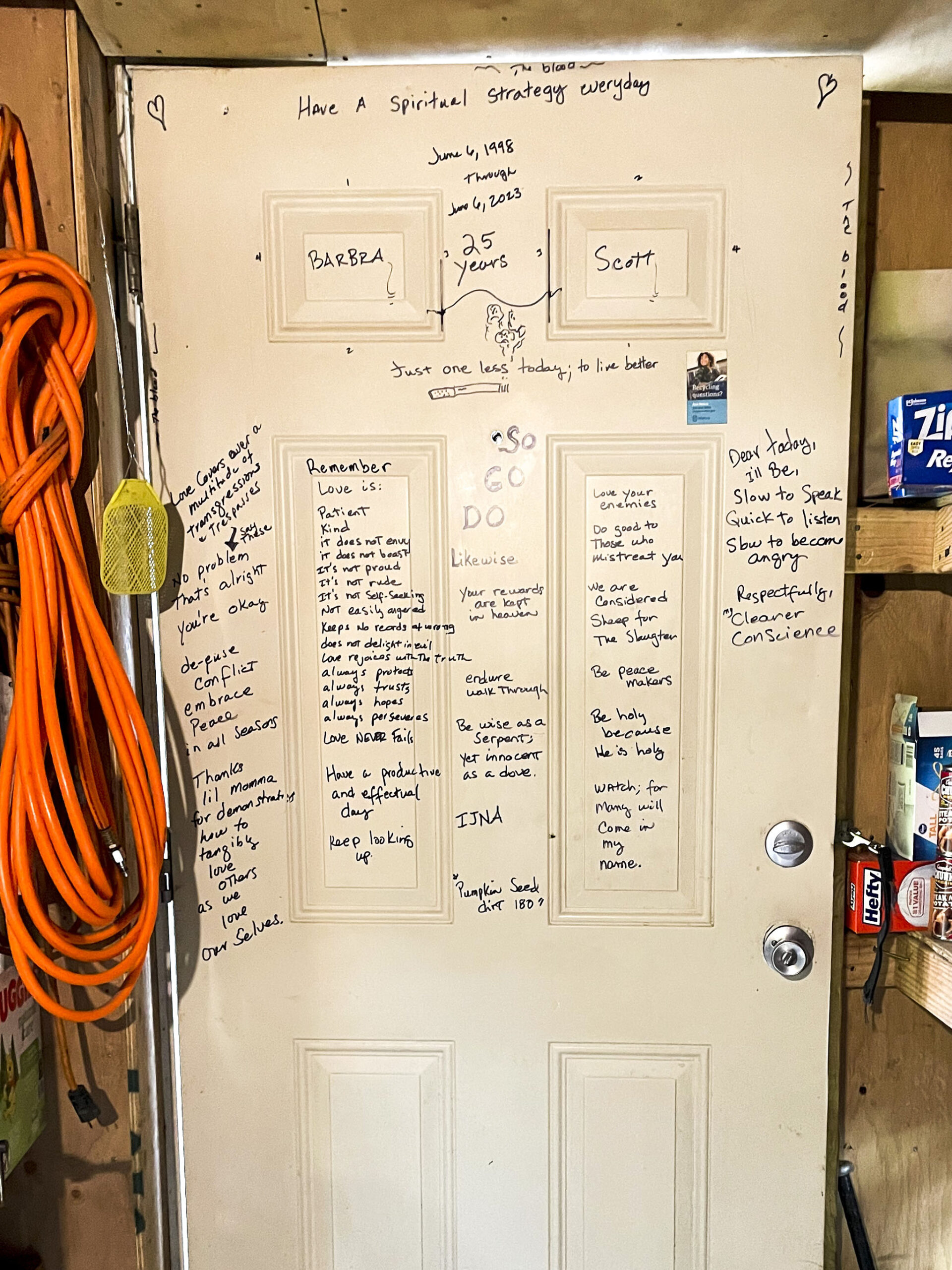

This is where we get into a little bit of a debate on the whole word of home. I don’t really claim any earthly home. I’ve never owned a home. I’ve never bought a home. And so for me to call this my home — I mean I have respite anywhere my ass hits is respite. And really, I mean that, but would I call this home? No. I feel like I have a home in heaven and that’s where I want to go.

I gave up the idea of buying a house and that “American Dream,” probably at about 30 years old. That just wasn’t going to happen for me.

I don’t carry anything more than what I can. I have a storage unit. I keep my stuff in.

This here is kind of an interesting thing. I bought this, this is a handmade…cigar electric…it’s electric actually. It’s keyed to like a banjo.

[SOUNDS OF ELECTRIC-CIGAR BOX BANJO PLUCKING]

My son died of a fentanyl and methamphetamine overdose a year ago. So James died August 12th of 2022 and he would’ve been 32 on August 21st, 2022. So just before his 32nd birthday, he passed away.

So you have several pictures of him around. When you’re living in a car, you typically don’t put pictures on the wall. You know, so that’s different. I still have some of his ashes, but his ashes are in my flower bed and then in the tree upstairs. It’s what keeps me going. Because I did think about giving up, but James wouldn’t have wanted me to do that.

[SOUNDS OF ELECTRIC-CIGAR BOX BANJO PLUCKING]

I’ve just been so resourceful, taking care of myself. I don’t rely on other people. I just can’t. And that’s one thing that I think is really broken. And a lot of us, especially ones that are, what we call “chronically homeless,” is everybody has failed me. Everybody has failed me. So when I got sick and tired of people failing me, I started picking myself up.

Weber describes the cafe as “someplace where you can be yourself — angry, dirty, and fully human,” without fear of discrimination or violence. “You could be a wreck, near death’s door, and you knew you could come to the cafe and get some help.”

TERAH BENNETT / NEXTGENRADIO

The original cafe is closed for now, but the nonprofit has bought a new building, and plans to reopen in the future.

At Sisters of the Road, Weber says she discovered the profound power of community. “That’s what we got from Sisters,” she says. “They [took] care of us, and they taught us how to take care of each other.”

This ultimate regard for others has become Weber’s driving purpose in life. “I want to make sure that people have just … somebody to care for them.”

Every night, she went to sleep serenaded by the cacophonies of overdose and withdrawal, police sirens and gunshots. Despite the sleep deprivation and hectic circumstances, Weber achieved a professionally impressive portfolio.

While her story comes across as one from “rock bottom to mountaintop,” Weber says it was her experiences on the street which allowed for her accomplishments.

“My life has been a rollercoaster,” she says. “But not the ones that go up and down. You know the ones that go side to side? My life is like that.”

TERAH BENNETT / NEXTGENRADIO

TERAH BENNETT / NEXTGENRADIO

TERAH BENNETT / NEXTGENRADIO

But now, Weber has overcome her disability and is a prolific public speaker. She’s testified before every level of government, including the United Nations. She advocates for the safety of impoverished people who rely on sorting through the waste of others for their income, who are frequently exposed to hazardous plastic waste.

Weber says she doesn’t regard her time unhoused with resentment, but with appreciation.

“[It’s] actually something I’m very proud of, because being chronically homeless doesn’t mean that I’ve lacked any success.”

This led her to found Ground Score from her tent, which was staked outside the cafe. Ground Score is a low-barrier employment program based in Old Town, on the same block as Sisters of the Road. Ground Score boasts a 60% rate of previously unhoused workers who have entered housing after being hired by the organization.

Weber now has established a residence in Hazelnut Grove, a village for previously unhoused folks located in North Portland. In the community she has goats, chickens, ducks, and pictures on her walls — all things she couldn’t have while living on the street.

While she now has a roof over her head, Weber still identifies as homeless, as she doesn’t consider her home to be of this world. “I don’t really claim any earthly home,” she says. “I’ve never owned a home. I’ve never bought a home.”

Weber says she would be willing to buy a house at some point, but has never been particularly attached to the idea. “I gave up on the idea of buying a house and that American dream probably at 30 years old,” she says. “That just wasn’t going to happen for me.”

Weber wants nothing to do with the conventional “American Dream.” Instead, she wants to cultivate community for the people who feel as she once did: out of options, and alone.

She cites Sisters of the Road as an inspirational example: “There were 50 people on that block [who went to the cafe]. Those 50 people … they’re inside. Isn’t that amazing?”

Weber says a lot of her desire to create reparative communities comes from what she observes when leaving her office at Ground Score every evening. “I don’t even have to walk two blocks down the street, and I’ll see somebody having a stroke. I’ll see somebody dying from a fentanyl overdose … This is every day. There shouldn’t be people suffering as bad as they are.”

“In my flower bed, I still have some of his ashes. There’s a little bit of James in every bit of my plants.”

Weber admits she’s considered resigning herself to the fate her circumstances have seemed to dictate—an existence mostly spent “in a line.” “If you [have] to spend eight hours a day finding a place to shower, clean your clothes, eat, all those things … [and] you get them from Social Services, that’s all your day is: living in a line,” she says.

“I did think about giving up,” she says. “But James wouldn’t have wanted me to do that.”

“There’s a song by Alice Merton…That’s me. I don’t have any roots in the ground.”

TERAH BENNETT / NEXTGENRADIO